Women’s history is American history. Black history is American history. Asian history is American history. Hispanic history is American history. Europeans were immigrants, too. Native American history is the original American story. So what is this crap they are teaching in schools as American history? Read more here. What should be taught? Read what the American Historical Association has to say about teaching history with integrity here.

What do you know about the Buffalo Soldiers?

Compare Thurgood Marshall with our current Supreme Court members. Sigh.

Who Really Discovered America? The question of who discovered America depends largely on how we define “discovery” itself. (more)

Claudette Colvin (a hero of mine), whose defiance of Jim Crow laws in 1955 made her a star witness in a landmark segregation suit, was overshadowed months later when Rosa Parks made history with a similar stand. Colvin was 15 at the time! Local civil rights leaders decided not to make Ms. Colvin their symbol of discrimination. She was, she later said, too dark-skinned and too poor to win the crucial support of Montgomery’s Black middle class. In 1956, Ms. Colvin was one of four Black plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle, a federal lawsuit brought against the city’s bus system. (more)

This is the third time the USA has expressed an interest in acquiring Greenland. The US previously tried to buy Greenland after the Civil War and WWII. In 1916, the United States formally recognized Danish interests in Greenland in exchange for the Danish West Indies, which became the U.S. Virgin Islands. (more) Its location between the U.S., Russia, and Europe makes Greenland strategic for defense and economic reasons. Greenland has reserves of oil, natural gas, and mineral resources, including rare earth elements. A poll conducted in 2025 showed that 85% of Greenlanders did not want to be part of the United States. (more)

In 1974, the Combahee River Collective was organized. It was an evolution from the more conventional National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO), which had been formed as a Black-oriented alternative to the National Organization for Women. Read more about this groundbreaking group of women here.

Who was Phillis Wheatley?

Ken Burns’ The American Revolution

Women in the US Military: Timeline

A few historical events that might not be taught today:

- 1863 New York Draft Riots

- 1513 Spanish exploration and colonization of the New World

- Republic of Franklin 1784-1789

- 1820 West Virginia Coal Wars

- 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

- The 1918 influenza epidemic

- 1878 Henrietta Wood wins restitution

- 1958 Onion futures trading ban

- Virginia Hall, WWII hero

- 1855 Elizabeth Jennings Graham

- 1871 Los Angeles Chinese Massacre

- Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676

- The Stonewall uprising of 1969.

- The Red Summer of 1919

- The Carolina Gold Rush of 1799

Do you know what Manifest Destiny is? You need to know, especially if you don’t remember learning about it in your middle or high school history class. Why is it important now? Because we are hearing manifest destiny language in our 21st-century political discourse!

What should be taught in American high school history classes? See what the American Historical Association thinks here.

1. Secondary US history teachers are professionals who are concerned mostly with helping their students learn central elements of our nation’s history. Teachers want students to read and understand founding documents to prepare them for informed civic engagement. They also want students to grapple with the complex history and legacies of racism and slavery. These goals are entirely compatible. We did not find indoctrination, politicization, or deliberate classroom malpractice.

2. Teachers make important curricular decisions with direct influence over what students are expected to learn. Despite legislative interference, the localized influence of state-mandated assessment, and efforts to standardize instruction, history teachers retain substantial discretion over what they use in their daily work.

3. Free online resources outweigh traditional textbooks, which are unlikely to stand at the center of history instruction. While publishers pitch digital licenses and tech tools to districts, teachers instead make prolific use of a decentralized universe of no-cost or low-cost online resources. US history teachers rely on a short list of trusted sites led by federal institutions including the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and Smithsonian museums.

American Lesson Plan distills insights gathered during a two-year exploration of secondary history education, combining a 50-state appraisal of standards and legislation with a close examination of local contexts in nine states. What did we learn? Secondary US history teachers are professionals who are concerned mostly with helping their students learn central elements of our nation’s history. Teachers want students to read and understand the founding documents to prepare them for informed civic engagement. (more)

Yale Announces 2025 Launch of the Yale and Slavery Teachers Institute

1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

During the Tulsa Race Massacre, which occurred over 18 hours from May 31 to June 1, 1921, a white mob attacked residents, homes, and businesses in the predominantly Black Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The event remains one of the worst incidents of racial violence in U.S. history. (more)

Did you know that¦

Here are some sites for more information about black history:

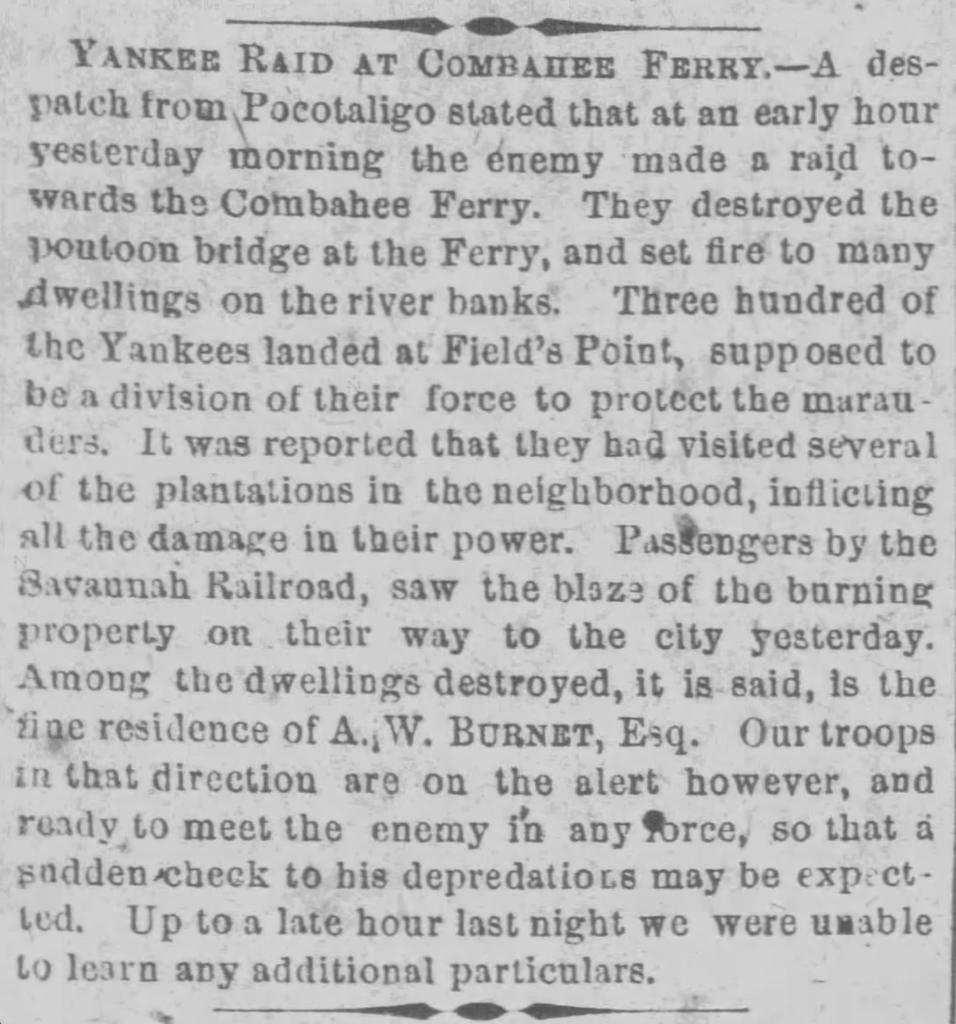

Harriet Tubman Becomes First Woman to Lead a Major US Military Operation

Harriet Tubman was an iconic freedom fighter known for her work as an abolitionist and conductor on the Underground Railroad. But did you know that Tubman was also the first woman to lead a major military operation when she helped execute the Combahee Ferry Raid during the Civil War? This South Carolina raid led to the rescue of more than 700 enslaved people and the destruction of several large rice plantations and Confederate military infrastructure. (MORE)

Do you know what the “Lost Cause” interpretation of Civil War history is?

Lost Cause is an interpretation of the American Civil War viewed by most historians as a myth that attempts to preserve the honor of the South by casting the Confederate defeat in the best possible light. It attributes the loss to the overwhelming Union advantage in manpower and resources, nostalgically celebrates an antebellum South of supposedly benevolent slave owners and contented enslaved people, and downplays or altogether ignores slavery as the cause of war (more). The National Park Service has numerous resources available to help people learn more about the Civil War.

In an address at Franklin Female College in Holly Springs, Judge Jeremiah Watkins Clapp, a former plantation owner and Mississippi state senator, urged the students “to see to it that our children shall not, at school or at home, shape their ideas or acquire their information and impressions from books or other sources of character calculated to poison their minds and their hearts and teach them lessons of humiliation and shame.†(more) Sounds a lot like the issues being raised over teaching history in 2023 to me! Many … writings are contained in the fourteen-volume series Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society (1898-1914).

A few historical events that might not be taught today:

- 1863 New York Draft riots

- 1513 Spanish exploration and colonization of the New World

- Republic of Franklin 1784-1789

- 1820 West Virginia Coal Wars

- 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

- The 1918 influenza epidemic

- 1878 Henrietta Wood wins restitution

- 1958 Onion futures trading ban

- Virginia Hall, WWII hero

- 1855 Elizabeth Jennings Graham

- 1871 Los Angeles Chinese Massacre

- Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676

- The Stonewall uprising of 1969.

- The Red Summer of 1919

- The Carolina Gold Rush of 1799